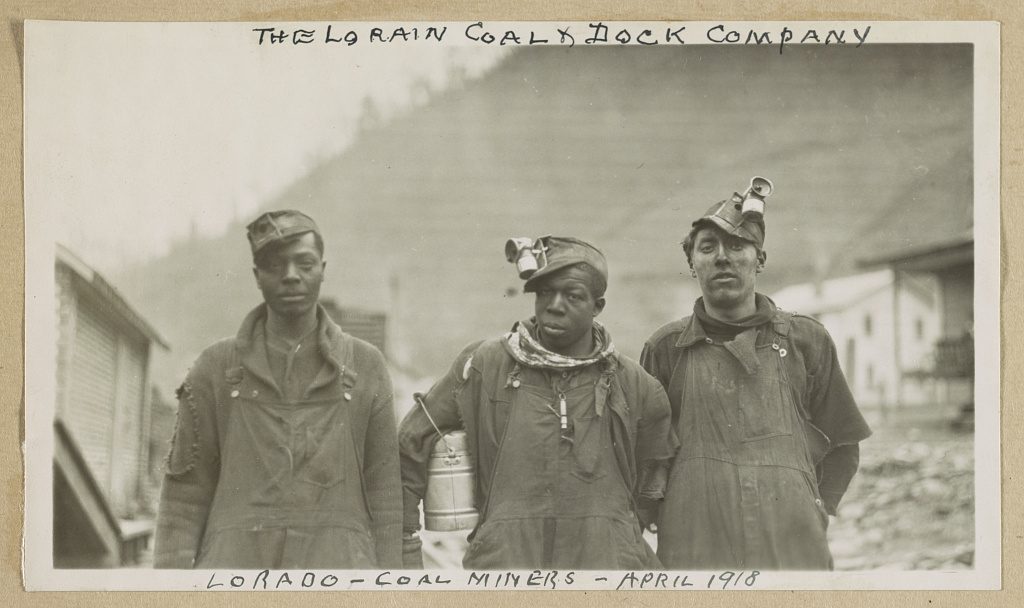

Picture a coal miner. Who do you see? Probably a man, face coated with coal dust, peering out from under a headlamp. Under the coal dust, you’d likely imagine his skin to be white.

At MWA, we work toward a more equitable future for our small corner of Appalachia. That includes many people who were (and still are) affected by the legacy of irresponsible mining practices throughout the industry’s history. Black Americans played an essential role in labor organizing and community advocacy in Appalachia and beyond.

In the mid-1700s, enslaved workers were among the first to work in America’s commercial coal mines in the coal pits of Richmond, Virginia. The Midlothian Mining Co., one of the largest coal companies operating in that state during the 1830s, used around 150 enslaved black workers.

After emancipation, coal companies actively recruited Black workers. By 1920, about 88,706 African Americans resided in central Appalachia. By 1930, 1 in 11 coal miners in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and West Virginia in 1930 were Black. Similarly, Black workers made up 13% of Western Pennsylvania’s steelworkers.

At the New River Gorge National Park and Preserve, displays tell the story of segregated housing, segregated schools, and unequal working conditions for Black workers, who took on the most grueling, dangerous, and deadly jobs. This was a strategy by the coal companies to keep the miners from unifying.

Despite these attempts to suppress unionizing, Black miners increasingly organized themselves to push for better working conditions and wages. In May of 1920, Black miners, white miners, and European immigrant miners banded together to stand up to the coal company. The conflict ended in a deadly exchange of gunfire known as the Matewan Massacre, resulting in the death of seven detectives from the coal company, the town’s mayor, and two miners.

During the Miners’ March of 1921 in West Virginia, African American miners made up a significant portion of the striking workforce. For five days from late August to early September 1921, some 10,000 armed coal miners confronted 3,000 lawmen and strikebreakers during the miners’ attempt to unionize the southwestern West Virginia coalfields when tensions rose between workers and mine management. The Miners’ March culminated in the dramatic Battle of Blair Mountain, the largest labor uprising in American history.

Even the areas of Appalachia with the smallest Black populations today were shaped by centuries of Black contributions. In the Central Appalachian counties of Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia—the predominantly rural subregion of Appalachia often considered to have little or no racial diversity—nearly one in six people were Black in 1820.

But the rise of Jim Crow segregation laws meant that Black miners faced increasing discrimination throughout the early 20th century. During the Great Depression, Black miners were often the first to be laid off. As mechanization of the mines increased throughout the 1950s, even more Black miners lost their jobs. Without jobs, these miners could no longer live in company housing. So Black miners and their families left the coal camps in search of jobs elsewhere.

The relative share of Black Appalachians has steadily decreased since then. Today under 5% of coal mine workers in the U.S. are Black. However, tens of thousands of Black people still call Appalachia home, including in its many rural counties.

In these areas, Black Appalachians are among those hardest hit during economic downturns. As their losses have been largely ignored, Black communities are disproportionately affected by economic distress and environmental damage. As we reflect on our region’s history and continue fighting for a more sustainable future, we can’t leave these populations out of the conversation.

Check out these other resources:

Read more about the day-to-day work of a Black coal miner in Helen, WV.

Follow these 15 Black Environmentalists!

Get involved! Check out the Black Appalachian Coalition and learn more about their work.