When I want to be deep in nature and far away from other people, I like to go for a long run in the Indian Creek gorge. Today I’m feeling antisocial, so I cruise down the gravel road to the gorge trailhead, across the road from Camp Christian. Sure enough, nobody else is here.

I stretch a bit, then jog over the first bridge and past the reservoir. Soon I’m surrounded on all sides by trees. Big tulip poplars, oaks, and mighty hemlocks reach up and over the wide path. Far below, Indian Creek rushes over the rocks, dropping into deep blue pools and flowing downstream to the Youghiogheny River. Birds flutter in the canopy, but otherwise the forest is quiet.

Further into the gorge, a chunk of stone wall peeks out of the underbrush. Half a mile later, part of an old railroad tie pokes out of the ditch. Finally I reach the end of the trail, where Indian Creek widens and slows to join the Youghiogheny River. I pick my way down the fisherman’s trail to the water’s edge and gaze up at the old stone viaduct that holds up the CSX railroad tracks along the river.

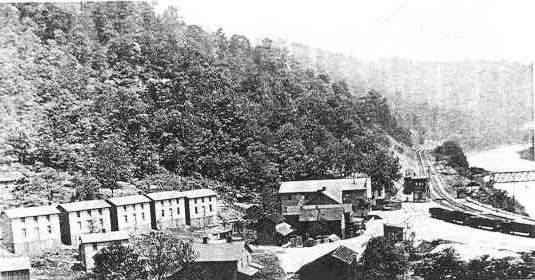

Aside from the trail, the forest surrounding the mouth of Indian Creek seems completely untouched. But the big stone viaduct tells another story. This structure is the only visible remnant of the town of Indian Creek, a bustling railroad depot that witnessed the boom-and-bust of the timber and coal industries in the Indian Creek Valley.

–

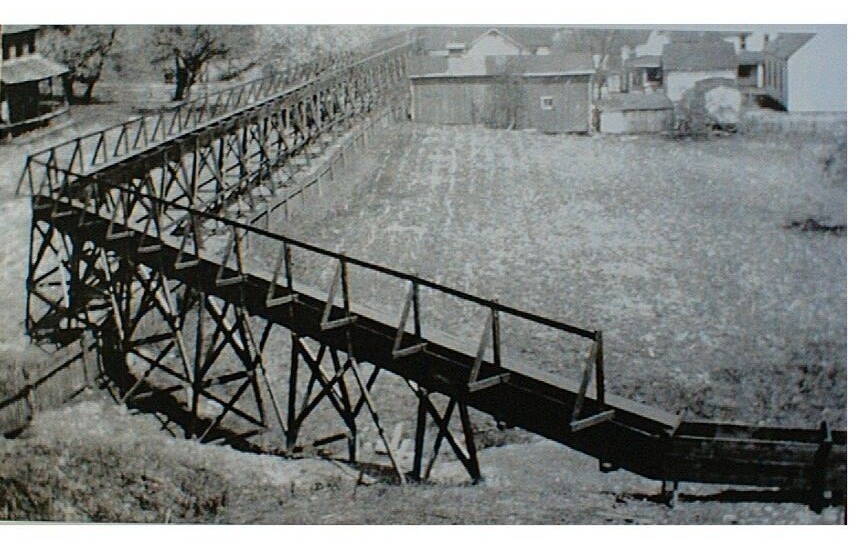

The Indian Creek Valley Railroad was chartered in 1902 by a group from Fayette and Westmoreland Counties. Shortly after, the Indian Creek Lumber company was formed to make use of the area’s vast tracts of timber and purchased 5,347 forested acres along Indian Creek and its tributaries for logging.

The railroad, which ran from Jones Mills to Indian Creek (where the creek meets the Yough), was finished in 1910. In its heyday, the 22-mile railroad had four passenger trains daily, two each way, that connected with the B&O at Indian Creek, seven miles from Connellsville. Daily freight trains carrying lumber and coal made for a busy track schedule.

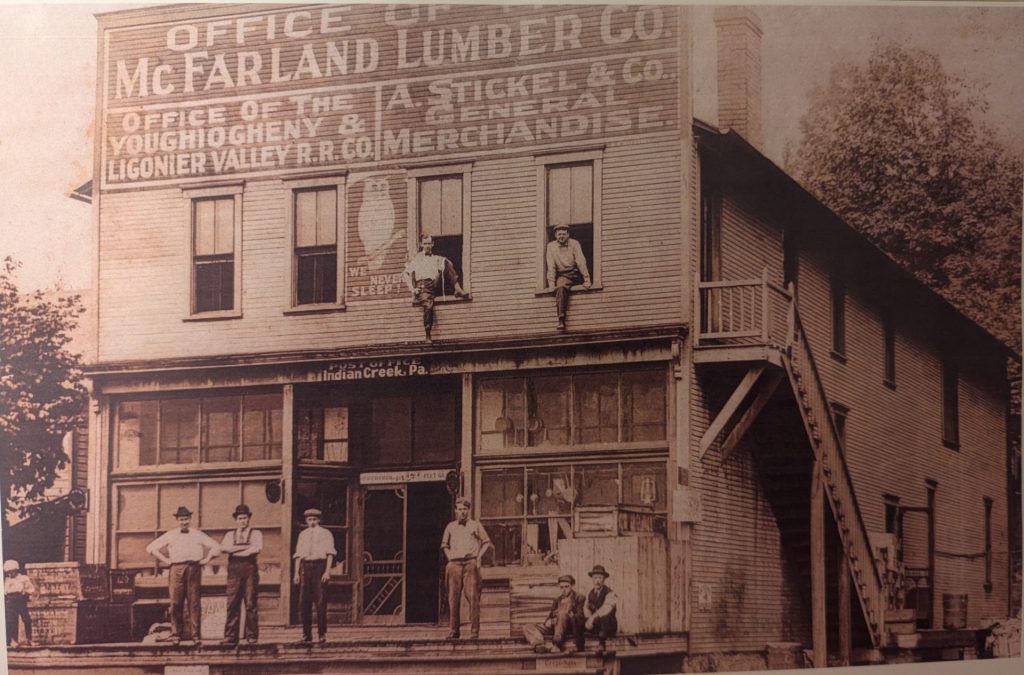

By that time, the town of Indian Creek was booming. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad built a station in the town, a general store opened, and employee homes went up left and right. A generator provided electricity to the town, and a huge tank stored water to power the sawmill, town, and the railroad. Scrap wood and sawdust were burned to feed to steam boilers. At its peak, about 200 people lived in Indian Creek.

A travel brochure bragged that in Mill Run “you will find most of [Mill Run’s] hospitable inhabitants at the station to greet you as the train pulls in.” The scenic Indian Creek station was featured on dinnerware used in B&O dining cars and on souvenir postcards.

The railroad company even built a sprawling, green recreation area called Killarney Park (where Camp Christian is today). Equipped with an inn, a baseball field, a dance hall, and ponds for boating, the park became a popular place for Pittsburgh residents to escape the city and get some fresh air.

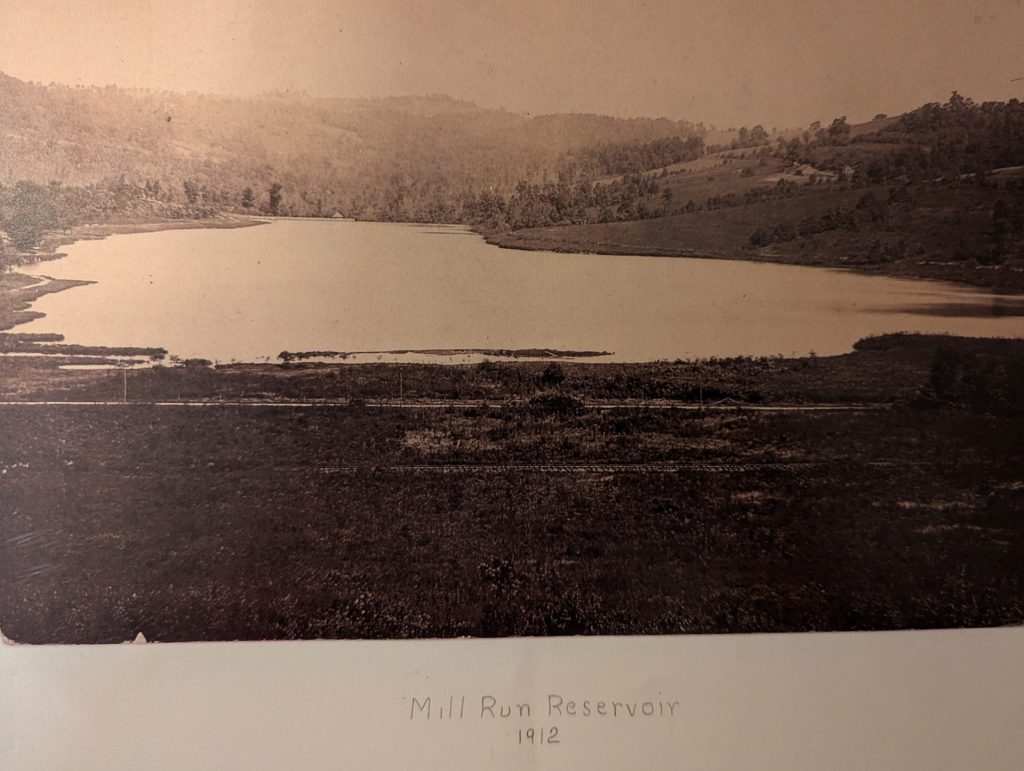

Around the same time, the Mill Run Reservoir was built. The 251-million gallon reservoir was a water supply for railroad operations, timbering work, and the communities that were quickly popping up in the area.

But people who relied on that water source started noticing the effects of upstream coal mining pretty quickly. The Pennsylvania Railroad Company, the Mountain Water Supply Company, the Dunbar Water Supply Company, and later the commonwealth brought a lawsuit against the local coal companies in the early 1920s – one of the earliest clean water cases in our watershed!

The plaintiffs argued that “The entire flow of the stream at the mouth of Indian Creek and at the dam, where the waters thereof are introduced into the pipeline, is and also has been pure, uncontaminated and of good quality, well adapted for domestic consumption and use and for supplying water for locomotive engines so it is alleged, until the recent wrongful action of the Defendant Coal Company and others.” They alleged that the water in Indian Creek had become too polluted to operate the steam engines, or to use for household purposes.

The plaintiffs convinced the court that mine discharges created a public/private nuisance and would destroy the water supply. The mining companies had to build a flume that transported all the water around the reservoir, ultimately discharging back into Indian Creek just before the confluence with the Yough in the gorge. We’re still dealing with the impacts of these discharges today.

In 1926, the B&O bought the Indian Creek Valley Railroad. As the mines in the Indian Creek Valley shut down one by one, the railroad became increasingly obsolete. People started moving out of Indian Creek, and the rail line was officially shut down in 1975, when the Melcroft mine closed. But the memory of the mines remained, along with their lasting environmental impact in the form of abandoned mine drainage.

In 1976, the railroad donated the 22-mile right-of-way to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy. This became the underlying structure of today’s Indian Creek Valley Trail.

–

As I jog back to the car, I notice some other rusty relics from the gorge’s industrial past. But I also pass a family hiking down to the creek with their fishing gear, a couple cyclists spinning down the trail, and a birder at the reservoir peering through his binoculars.

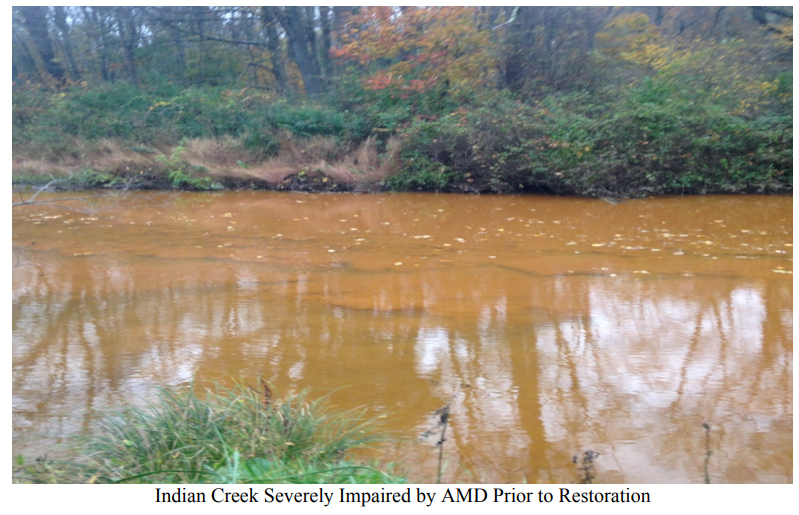

It’s hard to imagine this area as a busy industrial corridor, clogged with smoke and steam. But we’re not that far removed from the past – as recently as the 1990s, the water in Indian Creek was orange and toxic to aquatic life, thanks to the coal companies that exploited this valley over 100 years ago. Without MWA’s hard work to build the abandoned mine drainage treatment systems along Indian Creek, the water would still be polluted.

Back at the first bridge, I watch the stream flow past. The water is clear and cool. Little fish dart here and there, breaking the surface sometimes to sip a bug from the surface. For now, these places are a safe haven for nature once again.

Many of the reference photos used here were shared by a community member with a passion for local history. We’re grateful for their meticulous record keeping!